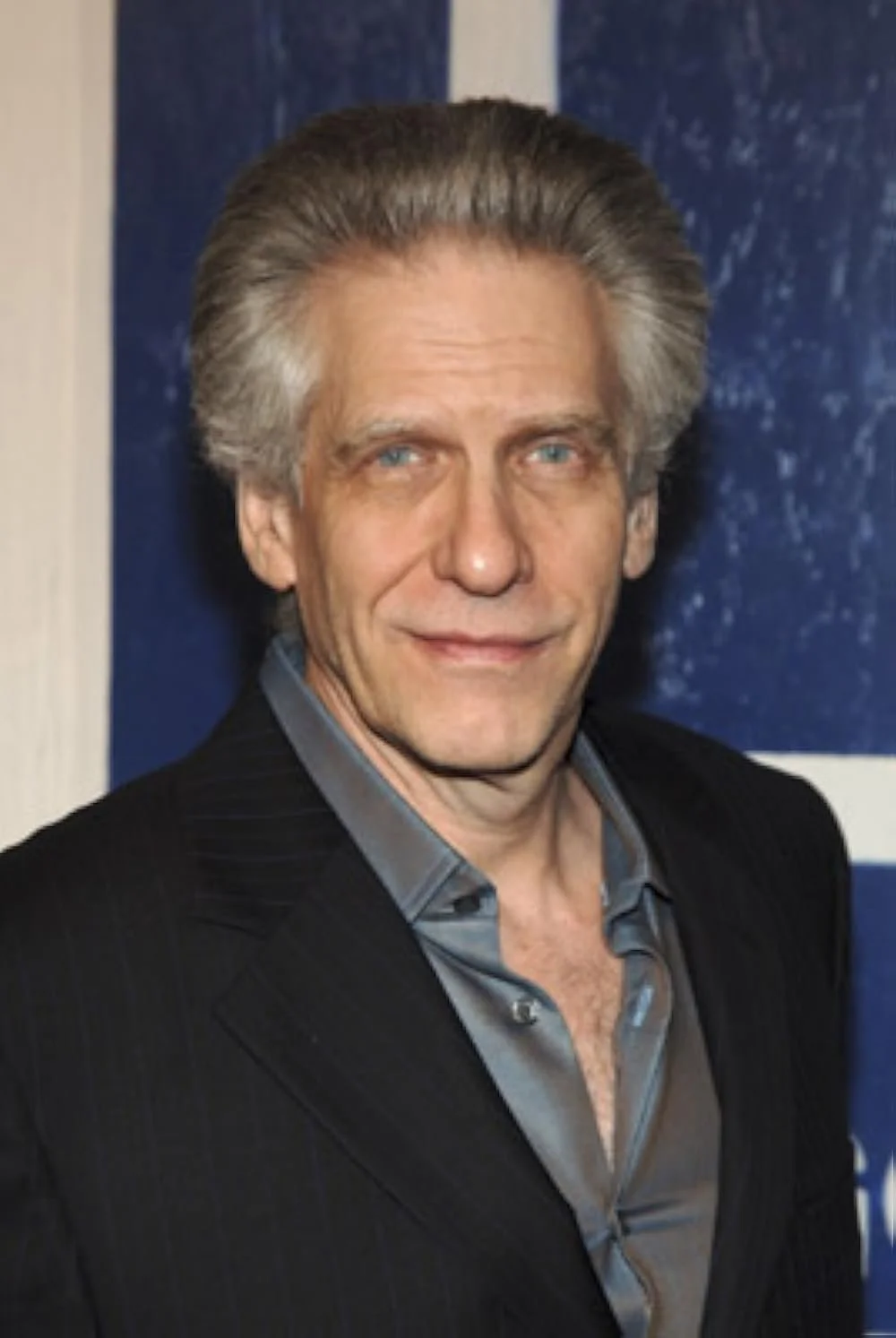

Original-Cin Q&A: David Cronenberg on Grief, Conspiracies, and Piercing the Veil of Death and Dying

By Liam Lacey

David Cronenberg’s new film The Shrouds (in theatres April 25) is about a Toronto entrepreneur named Karsh (Vincent Cassel) who invents a technology called GraveTech, which involves electrically wired burial nets and TV monitors that allow people to watch their buried loved ones decompose.

The premise combines many elements of the adjective “Cronenbergian,” a movie descriptor that conflates gruesome, speculative, cerebral, comic, and tender. The Shrouds is also a film rooted in the director’s experience. It began in 2017 following the illness and death of his wife of 43 years, the film editor and director Carolyn Cronenberg.

A scene from The Shrouds

Early in film, unknown persons desecrate gravestones in the GraveTech site, including that of Karsh’s wife Becca, sending him on a quest to find the perpetrators. Could they be environmental activists or data thieves working for Chinese government?

Were Becca’s doctors involved? Karsh seeks help from his brother-in-law Maury (Guy Pearce), an electronics whiz who was previously married to Terry, the lookalike sister of Karsh’s late wife (both women are played by Diane Kruger). There’s also a Hungarian billionaire and his wife (Sandrine Holt) in a film that spins a complex web of flashbacks, nightmares, and conspiracies.

I spoke to Cronenberg — always been one of my favourite interview subjects — last September, at the Toronto International Film Festival in a crowded temporary press room. A publicist warned me that the then 81-year-old director was hard of hearing, and we should sit close, which suited me because I have the same problem.

Cronenberg immediately noticed my hearing aid and we compared frustrations (jokes at parties we can’t hear) as we put our heads together. Not so close for Jimi Hendrix-style feedback, but close enough for communication.

I found myself thinking that hearing aids are Cronenbergian inventions: grub-like objects with tendrils sticking into orifices in the sides of the head. To quote the famous line from the director’s 1982 cult classic Videodrome, “Long live the new flesh.”

ORIGINAL-CIN: After watching the film, I was inspired to start looking around at what contemporary philosophers have to say about grief. There’s one Englishman, Matthew Ratcliffe, who wrote a book called Grief Worlds, where he talked about “the death of possibilities,” an experience somewhat like a phantom limb. Also, about “bereavement hallucinations” which is not like being high or psychotic, but that powerful sense of feeling the absent person’s presence. And why grief, unlike other emotions, is an ongoing state. I felt like these ideas resonated with what’s happening in The Shrouds.

DAVID CRONENBERG: I think that’s all true, but it doesn’t cover everything. I read all the books on grief, like C.S. Lewis and Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. And I found that I didn't relate to any of those things. I thought that it's interesting. It really shows you that grief is a specific, unique thing. Each grief is different, so making generalizations don't really get to the depth of it.

For example, Joan Didion talking about her husband's death felt to me very disembodied. She never talks about missing his body. She talks about missing his voice. She never once mentioned missing his body, and without going into thinking about, well, maybe they didn't ever have sex, I don't know, but for me, it was very bodily.

On an intellectual level, I understood what she said. But there were so many things that were so physical for me that didn't exist anymore, a feeling that I could never be attractive anymore, all kinds of strange things that I had never anticipated as being part of grief.

There are some things that I talk about in the movie that really were my personal reactions. I wanted to get into the coffin with my wife. It was very strong, and it took me by surprise. I really wanted to be in there and buried with her, not meaning to die, but I… I didn't want her to be there without me. I couldn't bear the idea that I wouldn't know what was going on with her. And that was really what gave me the idea for the movie.

But then, I have to say, as soon as you start to write a script, it becomes a fiction. And then you're inventing, despite the fact that there might be lines of dialogue and concepts that come from your actual recent life, suddenly it becomes a whole other process. People ask, ‘Was it cathartic to do that?’ And the answer is ‘No, not really.’ But it is satisfying in the way that being creative is satisfying, that you have the illusion of control. You're manipulating the world of the characters in a way that you cannot do in real life.

O-C: Which images came first?

David Cronenberg

DC: I definitely wanted the images of surgical mutilation as a representation of the medical intervention that happens when you have cancer or something like that. You know, amputations, surgery, surgical staples and all of that stuff, which were from my actual experience but I'm sure they're very familiar to a lot of people.

O-C: How did the idea of the electronic shroud arrive?

DC: Well, I started thinking, if I were a nerd entrepreneur who had some money — some influence, some experience of visual creation — and if I really wanted a connection with my wife’s dead body and didn’t want her to be alone in the grave, what would I do? And this is what I came up with, which this guy could do but I could never do because I’m not an entrepreneur.

O-C: I like the portmanteau “nerdtrepeneur.”

DC: Feel free to take it. OK, give me 10 percent. So, basically, that gave me the fictional entrée into the character and the situation, all of which is notably possible. This is not a science fiction movie, right? All the technology is available. You can absolutely create a version of the shroud. Maybe somebody seeing the movie will do that, some ‘nerdtrepeneur.’

O-C: It felt uncanny how the script overlaps the real-world panic about Russians and Chinese hackers and various conspiracies on the internet.

DC: You can't get away from it. I mean, there’s something in the air. I was thinking of a line by the character of Terry, played by Diane Kruger, who says to Karsh, ‘So that's your grief strategy?’ Part of it is paranoia and guilt. People say, ‘I should have done something. Something was going on with that doctor. He wasn't paying enough attention. Was the medication wrong? We should have gone to that clinic in Texas.’ Maybe you have regrets and if you can feel that you have penetrated the veil of death and dying is to say, ‘I know what's really going on.’ That's what gives you power. Anybody who is a conspiracy theorist feels that they have some special knowledge, some control. That can be very cathartic and soothing for somebody who's trying to deal with death.

O-C: You take that one step further with the character of Terry, who has developed it into a paraphilia, right? She is erotically turned on by conspiracies.

DC: An inventive conspiracy theory can be a rather attractive thing. You see someone on the internet come up with a really yummy conspiracy theory and they get a lot of followers, right? So, in a way, it’s an attraction that maybe has a little sexuality involved, because it’s empowering and exciting. It’s a matter of creativity. It’s like ‘I can come up with a conspiracy theory you never could have come up with.’ But as soon as I say it, people are going to start thinking it’s real. So, there’s a competition on a creative level.

O-C: So, to get this straight, what starts with paranoia about doctors and death blows up on the internet?

DC: Once you start, why stop? If you feel that there was some kind of conspiracy of doctors or scientists involved in the death of your loved one, why not explore it on a global level? Because why would they just be doing it to that one person? They must be doing it to a lot of people.

O-C: While we’re on conspiracy subjects, I assume the Hungarian billionaire was inspired by George Soros?

DC: No. It was thinking of Frank Stronach, a Canadian model. There was a little promotional documentary about him, talking in a similar way to my character, about his origins as an immigrant and how he built his empire building auto parts.

O-C: OK, another one. I had a theory about Karsh’s Japanese-style high-rise apartment, that it’s to the Buddhist concept of the nine stages of decay, where you contemplate a decomposing corpse to curb desire and remind yourself of impermanence.

DC: I wasn't thinking of that. It was more an idea from my novel Consumed [published in 2014]. A character goes to live in Tokyo and wants to become Japanese with a different culture and different perspective on life. So, I have this character played by Vincent Cassel, who sells this old home and creates an apartment that is rather Japanese. I was modelling that on the [producer-director] Niv Fichman's apartment. Another Canadian. He has a very Japanese-type downtown apartment not far from here. I almost thought we could shoot there. But, of course, we ended up on a film set.

O-C: What do you think is different about your mind from other people’s?

DC: My mind? I don't know. I mean, I don't have much trouble communicating with people, so I think I’m not that different. I think it's really a question of, if you’re an artist, what is different about you from someone who is not an artist? Because you have the same emotions and the same understandings, but what you do with those is different. You somehow you express yourself through creating something, whether it's a sculpture or a painting or whatever. I think that's the difference. But honestly, I don't think I'm that different from anybody else.

O-C. But you followed your curiosity.

DC: Well, curiosity — and being empowered to create. I think a lot of people are shy or hesitant or don’t think about it, but I was fortunate enough to be raised by parents who were both very creative, and to me, that was just normal that I should do that, too. Certainly, a lot of people who are not raised that way do become empowered some other way. But you have to be aware that you can do it and that it’s an exciting and fulfilling thing to do. That's the real difference.

O-C: I’m being told this is the end.

DC: That was very good.

O-C: Thank you. Good to see you.

DC: What kind of hearing aids do you have?

O-C: Oticon.

DC. Good brand.