Dance First: Waiting for a Better Bio of Samuel Beckett

By Liam Lacey

Rating: B-

Let me begin with a digression: Gabriel Byrne, who stars in the new Samuel Becket biopic Dance First, once told me he thought I looked like the Irish writer.

I was interviewing him for his role in David Cronenberg’s Spider and I responded that, to my mind, Cronenberg looked a lot more like Beckett. Byrne said he could see that, too. The point is, there are lots of men with bony faces and grey hair that stands on end, but there was only one Samuel Beckett.

Second digression: Long before my hair turned grey and wiry, another Irish actor, the great Richard Harris, told me in 1969 he had been invited to act in a play under Samuel Beckett’s direction, but he lost his nerve and cancelled the night before. He said he felt Beckett was “so extraordinary that he’d have to be marvellously ordinary in real life and I’d be disappointed” and “I’d never have anyone to look forward to meeting for the rest of my life.”

The point is that Beckett — the poet laureate of disappointment — should only be approached with extreme care.

This brings us to the film about Beckett’s life by James Marsh, best known for the Oscar-winning documentary Man on Wire and the multi-awarded Stephen Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything. Working from a script by Neil Forsythe, Marsh has created a superficially experimental if tame take on an artist of grim truths and dark comedy.

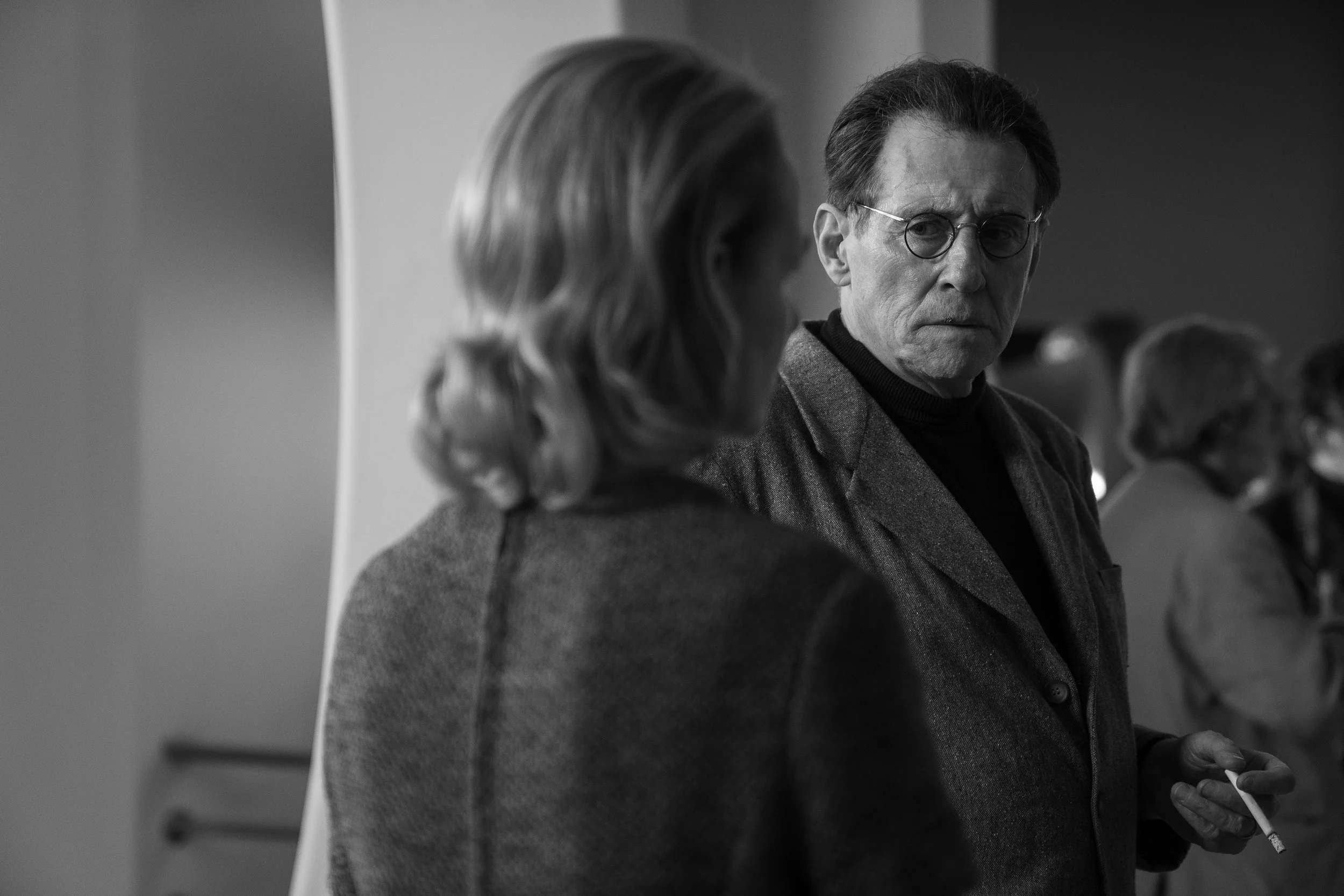

As such, it takes liberties that risk annoying those of us with a cursory knowledge of Beckett’s life while misleading those unfamiliar with his work. Clocking in at a brisk 100 minutes, mostly in black and white, the film features some good performances (led by a brooding Byrne, doing an impression of Beckett’s annoyed raptor profile), and a dramatic structure that initially intrigues before it wears out its welcome.

The opening scene sees Beckett in his early 60s with his wife, the French pianist Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil (Sandrine Bonhaire), sitting in a crowded auditorium in Oslo in 1969 where Beckett will receive the Nobel Prize. When it is announced, Beckett turns to Suzanne and mutters “What a catastrophe!”

Well, pardon moi. But Beckett famously did not attend the Nobel Prize ceremony (he was in Tunisia on holiday) and it was Suzanne who called it a “catastrophe” when they received the telegram from his publisher telling him he had won the prize, and they had better go hide from the media. (You can go on YouTube and watch his unorthodox “interview” on Swedish television, in which he stipulated that no questions could be asked.)

But the filmmakers have a strategy with this pseudo-historical opener, using it as a portal for an imaginative leap, or rather, imaginative climb. After snatching his citation from the King of Sweden, Beckett scampers up a pole on the side of the stage, emerges through the roof and exits in a grey rock-filled landscape.

There he meets another Samuel Beckett (Byrne again), dressed less formally. The two Samuels engage in a discussion about how and where to donate the prize money. “You know this is going to be a journey through your shame?” warns the second Samuel. “Isn’t everything?” the other Samuel responds.

From here, the two Becketts serve as our guides to the shame tour in a series of chapters illustrating several regret-filled relationships in Beckett’s life which are played out in chapters that turn to colour for the last chapter of Beckett’s later years.

This is a plausible way of framing Beckett’s imaginative world. His writing is replete with duelling interior monologues, circular self-questioning and here, the two Sams, evocative of Beckett’s quarrelsome stage duos, serve that purpose. No doubt regret was unquestionably a pervasive theme in his work. (“Personally, of course, I regret everything…” from the novel, Watt).

In practice, these sketches of Beckett’s emotional entanglements don’t prove all that illuminating about his career. In the chapter titled “Mother, May,” Lisa Dwyer Hogg is a gratingly one-dimensional scold, criticizing Sam as a child, and dismissing the young man’s literary attempts, when he is played by Fionn O’Shea as a gangly bespectacled student. There’s no mention here of the couple of years Beckett spent in psychoanalysis in England, dealing with his mother issues or the “savage love” he said she felt for him.

The second chapter, “Lucia” deals with the young Beckett’s journey to Paris where he stalks his literary hero, the famous Irish novelist James Joyce, in a café. (Fact check: They were introduced by a mutual friend).

At Joyce’s apartment, the older writer (Aidan Gillen) knocks back wine and bestows rather trite literary advice (“We must write dangerously, Beckett!”) while his wife Nora (Bronagh Gallagher), tries to push Beckett into a relationship with their mentally unwell daughter Lucia (Gráinne Good), who has a breakdown and is institutionalized after Beckett rejects her advances.

The real Lucia, who ended up institutionalized for most of her adult life, studied to become a professional dancer and performed several times. In the film’s version, she’s obsessed with doing the Charleston at various Paris nightclubs.

The next chapter, “Alfy (and Suzanne)” covers the years preceding and during the Second World War. Alfy was Alfred Péron, Beckett’s French teacher and friend who helped him translate part of Joyce’s Work in Progress (later Finnegans Wake) into French.

Beckett joined him in the French Resistance, but Peron died shortly after being released from a concentration camp. By implication, Beckett suffered from survivor guilt, though we barely have enough time with Alfy to appreciate the depth of their bond.

This chapter includes the beginning of Beckett’s relationship with his future wife, Suzanne (Léonie Lojkine), and the period they hid in a village in the south of France, digging potatoes by day and laying in ambush for Nazis who don’t show up, where Suzanne predicts she will never be as content.

An older and much unhappier Suzanne (Bonhair) appears again in “Suzanne (and Barbara),” covering a period in the 1950s when Beckett began an open affair with the BBC script editor, Barbara Bray (Maxine Peake).

In the film, Barbara gushes with delight that in Waiting for Godot “nothing happens,” to which Beckett responds, “Nothing happens twice.” (I might have been more impressed if I didn’t know that the quip was written by the Irish theatre critic, Vivian Mercier). The chapter culminates with a scene at the premiere of Becket’s 1963 one-act Play, a drama involving a man and two women in urns. Bonhair’s performance spits bitterness, briefly lifting the drama out of enactment mode into something angry and lifelike.

Dance First totters to a conclusion, as the hunched and elderly Sam Becketts confer again, and one reminds the other of his advice to a student, “Dance first, think later” which gives the film its title and makes a good T-shirt logo though it’s neither accurate nor Beckettian. (The line is adapted from Waiting for Godot, where the tramp Estragon says of the slave, Lucky: “Perhaps he could dance first and think afterwards.”

Dance First underestimates Beckett, who was not only a poet of anguish but also dry humour. Take the famous opening line from the novel, Murphy: “The son shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new.” Or this line from the short story, Dante and the Lobster: “His aunt was in the garden, tending whatever flowers die at that time of year.”

Depicting Beckett’s life without capturing that suave mordant spirit amounts to wrapping him in abhorrent sentimentality. Just the sad recollections of another old gent with a bony face and standup grey hair.

Dance First. Directed by James Marsh, written by Neil Forsythe. Starring Gabriel Byrne, Sandrine Bonnaire, Aiden Gillen, Bronagh Gallagher, Gráinne Good, Lisa Dwyer Hoff, Maxine Peak and Finn O’Shea. In theatres August 9 at the Carlton Cinema (Toronto), Gorge Cinema (Elora), Hyland Cinema (London), Bytowne Cinema (Ottawa), Bookshelf (Guelph, and Pac House (St Catharines).