First Man: Original and insightful take on haunted hero who landed the Eagle

By Liam Lacey

Rating: A

The increasing gap between critical hype - especially coming out of film festivals like Toronto - and the mundane reality of what appears at the multiplex a month later, isn’t helpful to either movies or credibility of critics.

Was that revelatory, transcendent cinematic masterpiece that swept the Tomato-meter overnight really any good? Sometimes, sometimes not. Let’s clear this up about First Man, the new movie from director, Damien Chazelle, starring Ryan Gosling as Neil Armstrong, the owner of the first human foot to leave an imprint in moon dust. It’s a good one.

That’s not to claim First Man is the last word in space movies (a genre that includes perennial critical and popular favourites 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Right Stuff and Apollo 13). But it is an original. even poetic, account of astronaut's Neil Armstrong's personal journey to stand on the lunar surface in 1969.

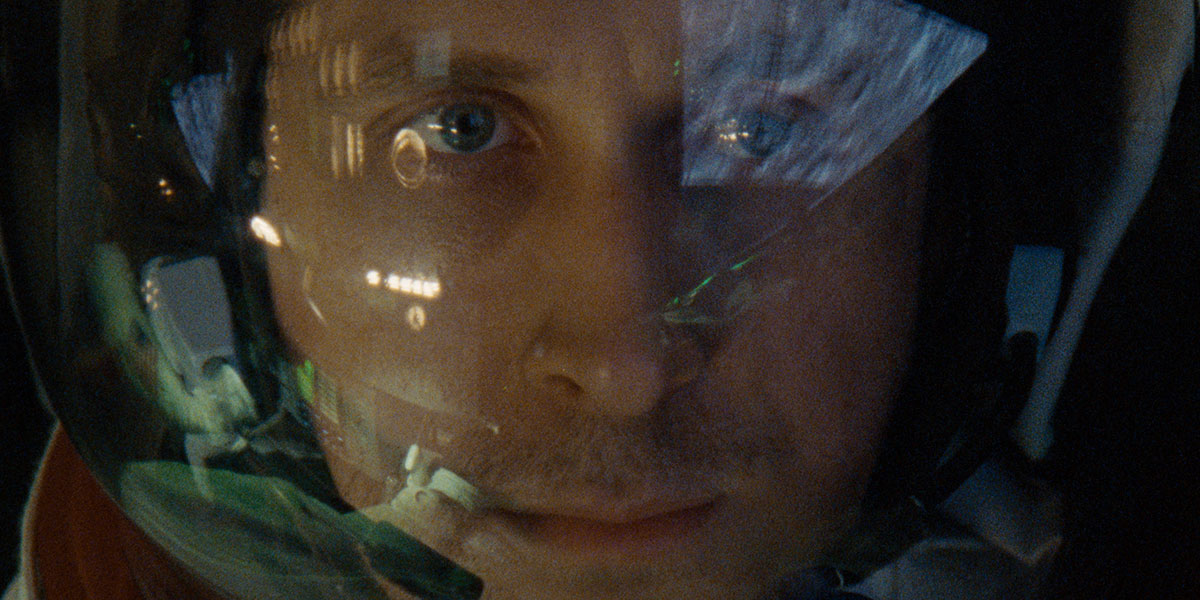

Ryan Gosling is both “spam in a can,” and a man trapped inside himself in First Man

Chazelle, the 33-year-old director of Whiplash and La La Land, confirms both his technical showmanship and versatility with First Man, He doesn't stint on visual intensity, including several teeth-rattling, white-knuckle bouts in cockpits and flight capsules. But the real wonder here is how much unexpected nuance there is in this character-driven, even haunted story, adapted by writer Josh Singer (Spotlight, The Post), from James R. Hansen's authorized biography.

A key here is a faultless, internalized, lead performance from Gosling (reminding us that, before he became a star, he was a very good actor) who plays Armstrong as a decent, emotionally-repressed Korean war vet and test pilot who deeply grieved the cancer death of his two-year-old daughter, Karen. In 1962, he moves from California to Houston to join the Gemini space program, taking in tow his redoubtable wife, Janet, played by The Crown's excellent Claire Foy, in a glum fifties’ bob:

“It’s a fresh start,” says Janet with forced cheerfulness. “It’ll be an adventure.”

The guys with the Right Stuff

From there, the movie follows Armstrong’s long, circuitous trip to the moon. In suburban Texas of the early sixties, they bond with his fellow straight-arrow astronauts and their wives: Patrick Fugit as the easy-going Elliot See, and his wife, Pat (Kris Swanberg); Jason Clarke as Armstrong’s buddy, Ed White and his spouse, Pat (Olivia Hamilton), and Corey Stoll as Buzz Aldrin, portrayed as comically obnoxious and ambitious.

Theirs is a Cold War world of determined conformity, with sudden ruptures of anxiety. Early on, there’s juxtaposition by the symmetry of the cockpit of the rocket-powered jet, and the MRI tube in which his daughter, Karen, was placed to scan her brain. The film makes us constantly aware of the astronaut’s experience of "space,” both the confinement (Chuck Yeager’s famous description of astronauts on the early mostly automated Mercury flights as “spam-in-a-can”) and the vertigo of staring into the void. Armstrong, in his capsule, is a man in a shell, trapped in another shell.

The movie also reminds us that Armstrong’s work repeatedly brought him a hair’s-breadth away from death while he strove to maintain a semblance of a normal life with Janet and his two boys. When Janet insists he explain to them that he might not return, he addresses them formally, ending, as if at a media briefing, with a curt request if they have further questions.

In retrospect, the man-on-moon goal, a propaganda mission to get Americans on the moon before the Soviet Union, seems irrationally expensive and precarious (While the movie doesn’t provide a lot of 1960s context, it earns bonus points for including Gil Scott Heron’s protest poem, “Whitey on the Moon.”)

Each test pushes the limits of technology. While presenting a cool, laconic front for the press and Congress, we get the sense NASA’s braintrusts were making it up as they go along: (“You’re just a bunch of boys making models out of balsa wood,” Janet explodes at one point.) Two years before the lunar mission, three of Armstrong’s colleagues, including White, are burned to death, trapped in the cockpit in pre-flight test for the first manned Apollo mission.

As for the moon, what’s new to say about it, except that here’s where the cost of an IMAX ticket pays off: The images that accompany that small-giant step are charged with a sense that we have entered a sublime dead zone, a lonely, monochrome wasteland, utterly silent (the sound drops out entirely) far from the tumult of human life, an amalgam heaven or hell.

Chazelle mentioned, during his recent visit to the Toronto International Film Festival, that he shaped the movie while thinking of the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, the hero’s journey to the underworld to rescue the dead.

Similarly, both Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity treat space quests as journeys filled with grief. First Man is not allegorical in the way those films were, but it does offer a strikingly different idea of heroism than we’re used to, unrelated to comic book bravado or facile patriotism. (Donald Trump has vowed not to see the movie because it doesn’t show Buzz Aldrin planting the American flag.).

In Chazelle’s film, Armstrong possesses none of the sense of destiny that Tom Wolfe ascribed to astronauts in The Right Stuff, “the belief that you were one of the elected and anointed ones”.

Rather, it’s a movie about a decent guy, gifted with a set of skills, moved by forces he doesn’t understand and a terrible need to accomplish something that matters.

First Man. Directed by Damien Chazelle and written by Josh Singer, based on a book by James Hansen. Starring: Ryan Gosling, Claire Foy, Jason Clarke, Kyle Chandler, Corey Stoll and Patrick Fugit. First Man plays at the Scotiabank Theatre, Empress Walk and Queensway Cinemas and Silvercity Yorkdale.